An Enduring Quest for Remembrance and Reconciliation

The 23.5 Hrant Dink Site of Memory in Istanbul sheds light on dark chapters in Turkey's history through the story of one remarkable man.

Dear readers, I hope all of my fellow İstanbullular have recovered from the jolts of this week’s earthquake. And I hope the scare has prodded you – if you haven’t already – to get together an earthquake kit and make some emergency plans with friends, family, and neighbors. This goes for all of you in the many other quake-prone parts of Turkey and in other countries too 🧿

Amid the hustle and bustle of Halaskargazi Caddesi in Istanbul’s Şişli district, a black stone engraved in Turkish and Armenian sits unobtrusively in the sidewalk in front of the Sebat Apartment. From 1999 to 2015, this graceful early 20th-century building was home to the offices of Agos, the first newspaper in Turkey to publish in both Turkish and Armenian. The stone marks the spot where the paper’s editor-in-chief, Armenian-Turkish journalist Hrant Dink, was assassinated on 19 January 2007.

In 2019, Agos’s former offices were reopened to the public as the 23.5 Hrant Dink Site of Memory, a space for remembering this remarkable man and the long struggle for Turkish–Armenian reconciliation and minority rights that cost him his life. Honoring the site with an award in 2023, the European Museum Forum described it as a “pendulum between pain and hope.”

That tension is present in the site’s unusual name, which refers to two dates marked this past week: 23 April, the National Sovereignty and Children's Day holiday in Turkey; and 24 April, the day in 1915 when more than 200 Armenian intellectuals and public figures were arrested in Istanbul, an event that is considered the start of the genocide of the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian population. Turkish history tells the story differently, and attempts to commemorate this latter date have been banned in recent years.

In a column he wrote in 1996, Dink envisioned the date of 23.5 April as a sort of liminal space for resolving the dilemma he described as “to be both Armenian and from Turkey; to experience the holiday of 23 April with all its fervour and to partake in all the grief of the following day.”

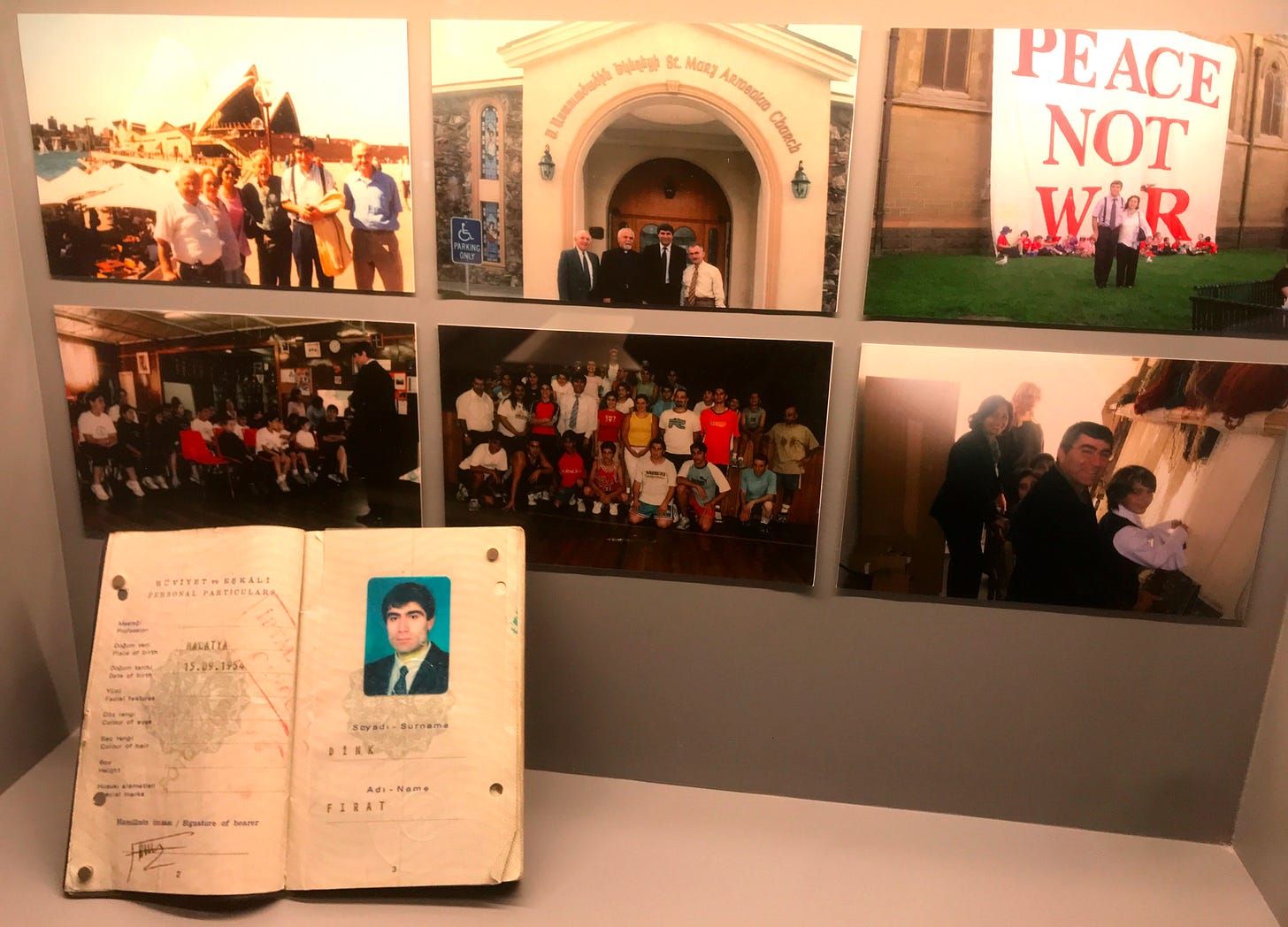

That article is one of many texts by Dink reproduced as trilingual leaflets throughout the memory site, which also features a wealth of videos, documents, photographs, and digital archives related to Dink’s life, the founding of Agos, court cases filed against Dink, and the ongoing fight for justice for his murder, all of which shed light on the larger story of Armenians in Turkey.

Leading a tour through the site, program coordinator Aslı Yolcu pointed out displays of Dink’s passport and old business cards bearing the first name “Fırat” instead of “Hrant,” and noted that many Armenians as well as Kurds still have a second, Turkish, name to use in situations where they might face prejudice. The “Tırttava” room, lined with corrugated metal, serves as a studio where visitors can record their own experiences with discrimination – whether as women, members of the LGBTQ+ community, or part of a religious minority – and listen to others’ stories.

“It’s a way to feel like we are not alone in Turkey,” Yolcu explained.

The “Toilet Choir” installation meanwhile speaks to the brutality of the 1980 military coup, while a room housing the archives of Agos includes ads that Armenians placed in the paper trying to find information about relatives who might have survived the genocide, often with their true identities stripped away. A room devoted to Camp Armen in Tuzla, an Armenian orphanage where both Dink and his wife Rakel spent summers as children, also memorializes the campaign to return the property to the Armenian community after it was expropriated by the state.

Dink’s office has been preserved as he left it on the day he was murdered, with walls covered with photographs and paintings reflecting different aspects of Armenian culture, shelves full of his personal library – and a TV showing clips of the horse races that he loved to watch and bet on.

An enclosed balcony behind Dink’s former office is home to a reverent, chapel-like installation by the Istanbul-born Armenian conceptual artist Sarkis, who filled the cracks in the walls using the techniques of kintsugi – a Japanese art form in which broken pottery is repaired with gold-dusted lacquer. The central piece, “Salt and Light,” consists of a neon sculpture in the shape of the main building at Camp Armen suspended above a metal fire ring containing a perpetually lit oil lamp and a small bowl of salt.

For the artist, who often works with neon, the material’s pulsing quality is reminiscent of a heartbeat, according to Yolcu. The heart of Hrant Dink is definitely still beating here.

The 23.5 Hrant Dink Site of Memory is located at Halaskargazi Caddesi No.74/1 in the Sebat Apartmanı in the Osmanbey neighborhood of Şişli. It is open to visitors Tuesday through Friday 10am to 5pm, Saturday 10am to 6pm, and Sunday 11am to 6pm. Admission is free and an online virtual tour is also available.

I was one of the project coordinators of this amazing memory site for four years. We built it with great efforts and dedication with so many people. It was a great honor for me personally.