Protests, Culture, and Power

As people in Turkey take to the streets and call for boycotts, will the country's art world come under increased pressure to take a stand?

Swept up in the masses of people pushing their way down a broad city street toward the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (İBB) headquarters, part of the largest wave of protests in Turkey since the Gezi Park resistance in 2013, the cultural legacy of those earlier demonstrations was impossible to miss.

Similar chants and songs echoed through the crowd, many of whom carried placards exhibiting the same kind of clever wordplay and riffs on current events and pop culture that were on display more than a decade ago. Some directly referenced Taksim Square, the locus of the previous protests, and being the “children of Gezi.” (One young protester I spoke with briefly as we fled oncoming tear gas later in the evening said he had been just nine years old in 2013.) There was even a “dervish” in a gas mask and people reading books in front of police lines.

These new protests have been ongoing in Istanbul and other cities around Turkey since Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, a prominent opposition politician, was detained on 19 March and subsequently arrested on alleged corruption charges. Many other figures from the municipality and its affiliates have also been arrested or detained, including İBB Deputy Secretary General Mahir Polat, who has led an extensive culture and heritage restoration campaign in Istanbul, and Murat Abbas, General Manager of Kültür A.Ş., which organizes concerts, exhibitions, and other cultural events in the city.

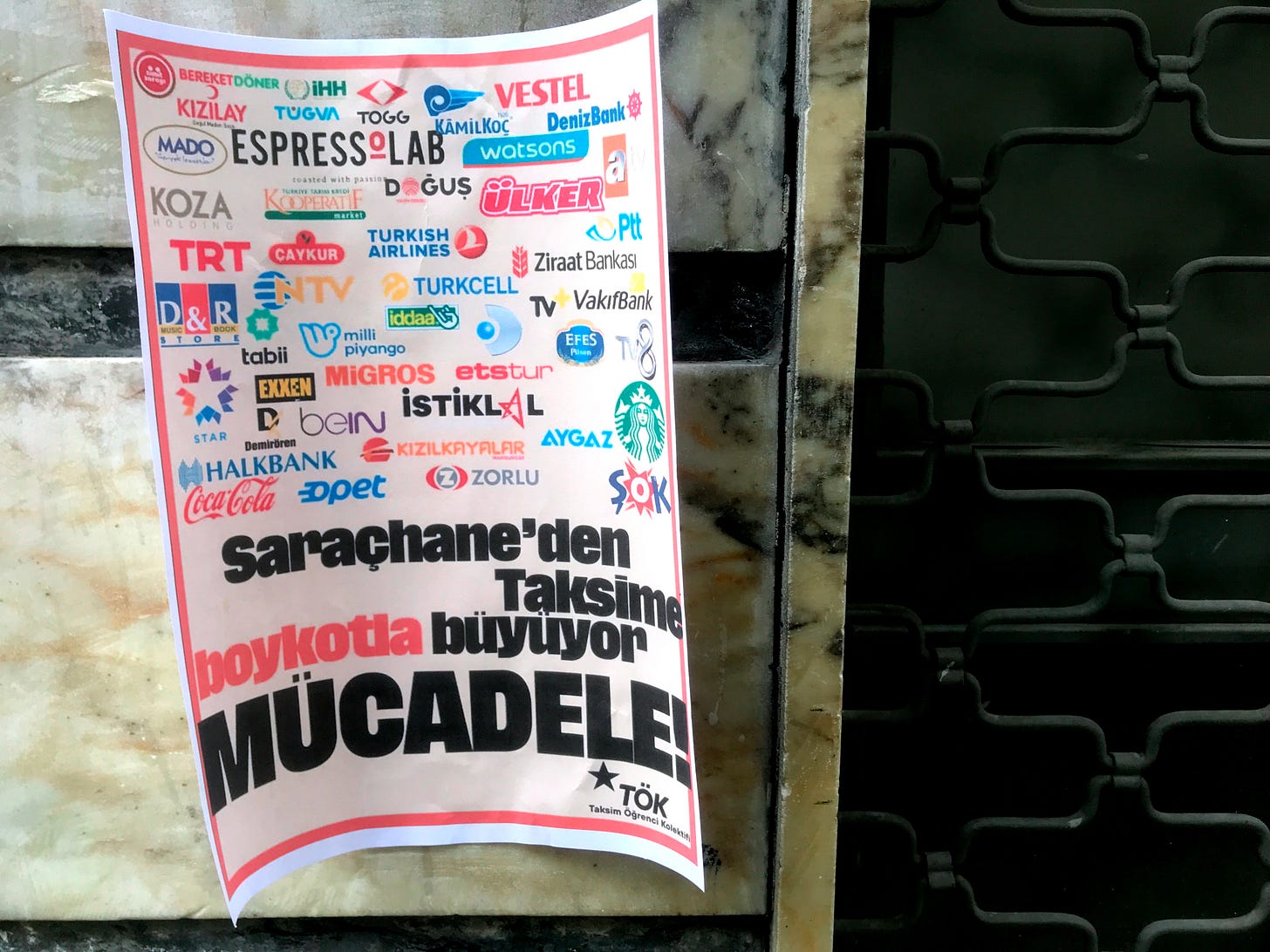

Despite the many moments of Gezi déjà vu, the current demonstrations are taking place in a different Turkey, a more unequal, impoverished, and repressive one than it was in 2013. But while many have been getting poorer in the ensuing decades, others have continued to get richer. Some of that wealth is now being targeted by protest organizers and individual activists who are calling for people to boycott a wide range of businesses in addition to taking to the streets.

The listed companies are generally either directly linked to members of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s ruling party (mostly prominently Espressolab, a cafe chain owned by relatives of Istanbul’s former mayor Kadir Topbaş) or ones that are seen to have muzzled news channels that they own in order to continue profiting from close ties to the government through contracts in key sectors like construction and energy.

These complex networks of businesses controlled by large holding companies in Turkey were visualized as vast interconnected webs by artist Burak Arıkan as part of the Mülksüzleştirme Ağları (Networks of Dispossession) project, which was initiated during the Gezi protests and first exhibited at the 13th Istanbul Biennial later that same year. (That biennial was itself the subject of pre-Gezi protests for receiving funding from companies involved in controversial “urban transformation” projects, and post-Gezi criticism for retreating from the public sphere.)

While the silence and censorship of corporate media outlets has been the main driver of the current boycott calls, Turkey’s major art institutions are often part of these same webs. As one independent curator and writer explained to me while I was working on a story on political pressures in Turkey’s art world a few years back:

“Before the 1980 military coup, the arts were predominantly supported by the state; the transition from public to private money started after that and gained traction in the mid-2000s. In the early 2010s, there were several large censorship scandals and people were shocked, but why? The private money is always entangled with the state.”

Individual artists, writers, and other cultural workers are, of course, present at and documenting the protests; some also signed on to collective statements against İmamoğlu’s arrest and police violence toward demonstrators. An independent LGBTQI+ arts and culture platform has been posting lists of each day’s planned protests, around Turkey and internationally. The magazine ArtDog and the gallery FotoğrafEvi have announced that they will no longer have their publications stocked at D&R, a chain bookstore included on boycott lists.

The overall response to the ongoing protests from the art establishment has perhaps unsurprisingly been rather muted, however. The social-media accounts of many large cultural institutions seem to have gone silent since 19 March. A full week after the protests began, Instagram was suddenly abloom with carefully worded solidarity statements from galleries and art initiatives, which were met with a mix of applause emojis and “too little, too late” sentiments in the comments section.

So far no arts and culture-related institutions, businesses, or venues seem to have been specifically included on the main boycott lists, even those intertwined in different ways with large corporations that are, like the Doğuş Group (which developed both Galataport and Bomontiada). But as discontent grows with those across society who are seen as “staying silent,” an arts and culture scene already battered by the ongoing economic crisis, beset by a transparency controversy that rocked the Istanbul Biennial and related institutions, and facing increased cultural politicization and conservative backlash could end up caught between its moneyed backers and public demands to take a stand.